In the current collection, the title character in “Olfert Dapper’s Day” (an actual historical figure) finds himself in Maine in exile from his comfortable life as a travel writer and physician (both professions thoroughly fake) in Holland.

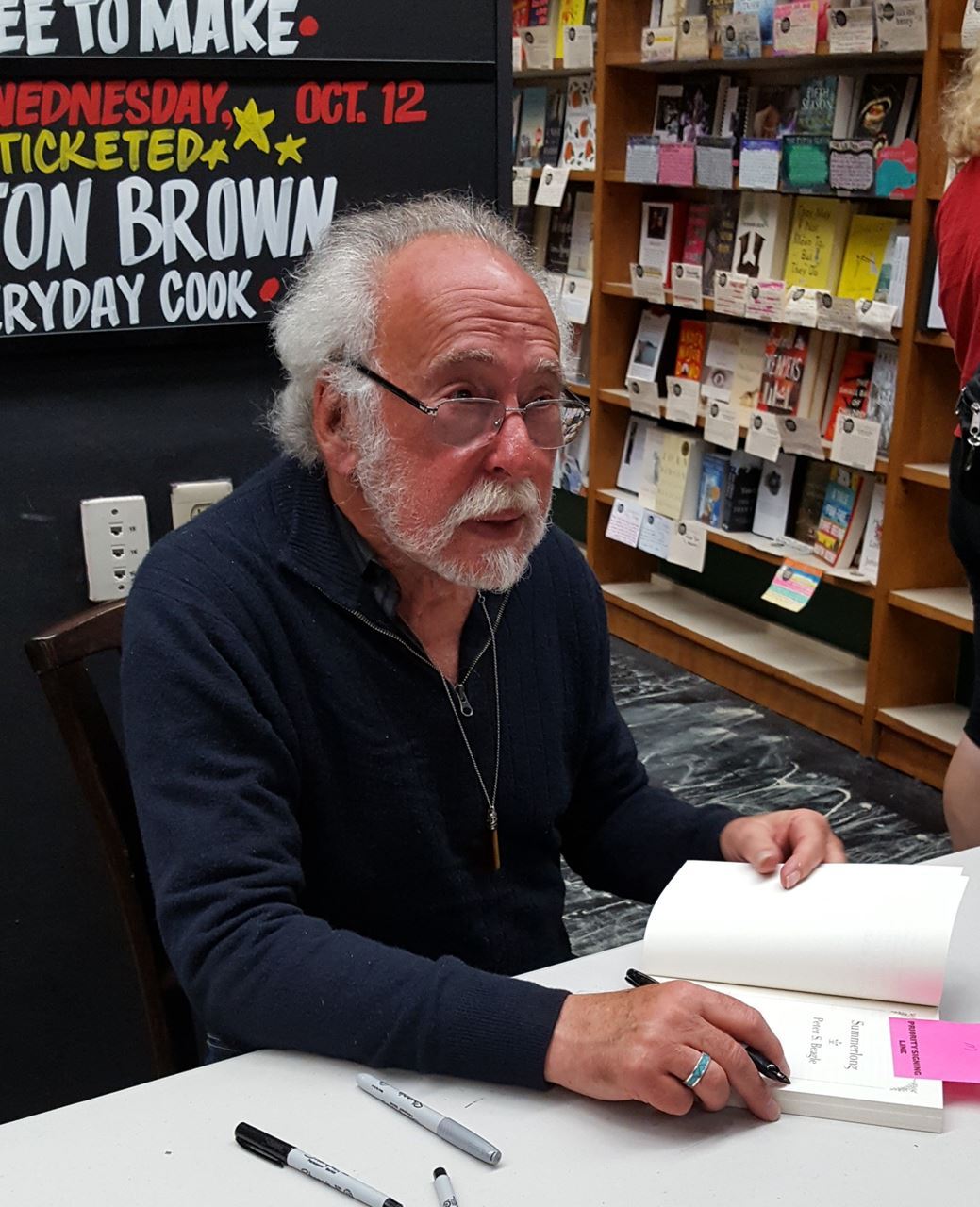

Some themes recur across a variety of settings and stories, though, and one of them is Beagle’s deep empathy for characters who, their aspirations mostly behind them, nevertheless encounter something marvelous – the retired history professor in Summerlong, the poet-turned farmer in In Calabria, even the homeless dropout and just about all the ghosts way back in A Fine and Private Place. For the most part, Beagle is less visible in these tales than in many of his more recent ones, although there is a rather touching tribute to his old friend Avram Davidson in “The Way It Works Out and All”, in which Davidson’s famously mercurial and far-reaching mind is translated into actual geography, as Davidson sends postcards from places he could not possibly have been, having discovered a kind of subreality called the “overneath.”

His new collection, The Overneath, tends toward the latter, with two more Schmendrick stories (“The Green-Eyed Boy” and “Schmendrick Alone”, to go with earlier stories like “The Woman Who Married the Man in the Moon”), three tales that deal with different varieties of unicorns (Chinese in “The Story of Kao Yu”, Persian in “My Son Heydari and the Karkadann,” North American in “Olfert Dapper’s Day”, in which an exiled quack Dutch physician thinks he sees one in 17th-century Maine), and one story set in the world of The Innkeeper’s Song (“Great-Grandmother in the Cellar”). Beagle’s late career has been something of a marvel, shifting between deeply resonant and apparently autobiographical fictions like “The Rabbi’s Hobby” and “The Rock in the Park” (both in his earlier Tachyon collection Sleight of Hand) with occasional revisits to the greatest-hits territory of The Last Unicorn or The Innkeeper’s Song.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)